Solidarity, ambition & rapid mobilization needed to achieve climate security

COP27 delivers historic breakthroughs, but does not formally raise ambition for the speed of decarbonization efforts.

The COP27 United Nations Climate Change negotiations in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, remind us of the urgency of climate action by their very location. The region is extremely arid, with many countries facing severe water and food scarcity challenges. Climate-related destabilization—driven by slow-moving disaster, like prolonged severe drought—affects tens of millions of people across the region, and the cost of everyday impacts is rapidly piling up.

Addressing Loss & Damage

The COP27 achieved the major historic breakthrough most said would be necessary, and yet seemed unworkable: A consensus agreement to create a fund to address climate-related loss and damage, particularly for the most vulnerable and resource-stressed countries. The commitment to create a fund is a breakthrough, but so is the establishment of a Transitional Committee to inform the design of the funding facility and to coordinate the earmarking and mobilization of loss and damage response funding through existing institutions, over the coming year.

The big question about loss and damage is not whether this money will be spent; the big question is whether it will be spent wisely, in a way that rescues the most vulnerable from unconscionable hardship, or whether it will be spent wastefully after horrific loss of life, just to achieve the effect of treading water in a deeply destabilized future. The Loss and Damage Fund is a decision to spend more wisely, save lives, and prevent costly and uncontrollable destabilization.

Reforming finance to value vulnerability & resilience

The Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan—the formal COP27 outcome agreement—also calls for comphrensive operational reform of multilateral development banks (MDBs) and international financial institutions (IFIs). The projected reforms are needed to better account for vulnerability and related spending needs, uneven climate risk, and the foundational value of mitigation, adaptation, and resilience measures. The text also calls for developing:

“a new vision and commensurate operational model, channels and instruments that are fit for the purpose of adequately addressing the global climate emergency, including deploying a full suite of instruments, from grants to guarantees and non-debt instruments, taking into account debt burdens, and to address risk appetite, with a view to substantially increasing climate finance;”

The COP27 is the first to agree to such institutional reforms to value vulnerability, a recognition of the need for climate-aligned debt relief. The text effectively recognizes the limits of debt-based climate finance, due to the systemic nature of “interlinked global crises [like] climate change and biodiversity loss” and their connection to “Stresses that the increasingly complex and challenging global geopolitical situation and its impact on the energy, food and economic situations”.

The systems lens

The system lens is referenced for food, energy, and finance, though in different ways. This is no small thing, as nations and communities across the world are faced right now, today, with urgent short-term decisions about how to secure basic supplies in a time of scarcity and soaring prices. The emerging systems transformation consensus—even if it lacks the urgently needed details about next steps—lays a foundation for future work towards successful climate resilient development.

The Preamble concludes with a detailed and specific admonition that efforts to meet short-term food, energy, and finance needs, or to achieve recovery from the coronavirus pandemic, “should not be used as a pretext for backtracking, backsliding or de-prioritizing climate action”.

The Preamble also highlights the need for “sustainable lifestyles”, including modes of consumption and production, as well as the need for “an approach to education that promotes a shift in lifestyles while fostering patterns of development and sustainability based on care, community and cooperation”. This is not, as has been feared in the past, a way of shifting responsibility to individuals; it is, instead, a signal that Parties are in agreement about the need to surround consumers with better choices and move toward incentives and investment practices that favor a circular economy model.

Energy transition

The great disappointment for many is the language around mitigation, or decarbonization of energy systems. A diverse coalition of countries, including Tuvalu, the United States, and India, nearly achieved a de facto fossil fuel non-proliferation agreement, with language that called for the phase out of all fossil fuels, naming coal, oil, and gas explicitly. That language was replaced, however, with softer language (in paragraph 16, under section IV. Mitigation), which calls for:

“accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.”

In the Energy section, above Mitigation, the text cites:

“the urgent need for immediate, deep, rapid and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions by Parties across all applicable sectors, including through increase in low-emission and renewable energy, just energy transition partnerships and other cooperative actions.”

Taken together, this language worries many, who see “low emissions” as code for natural gas, and note the word “increase” as a signal that countries intend to increase their reliance on natural gas. It is important to note that any natural gas system that leaks methane cannot be considered “unabated” or “low emissions”, and the Sharm el-Sheikh text—as noted above—warns against “backtracking, backsliding or de-prioritizing climate action”.

The cost to all of us of getting that wrong, and letting climate emergency run away unchecked, would be intolerable. Financial institutions and regulators will have little choice but to find ways to identify and prevent that kind of destructive activity.

What about 1.5ºC?

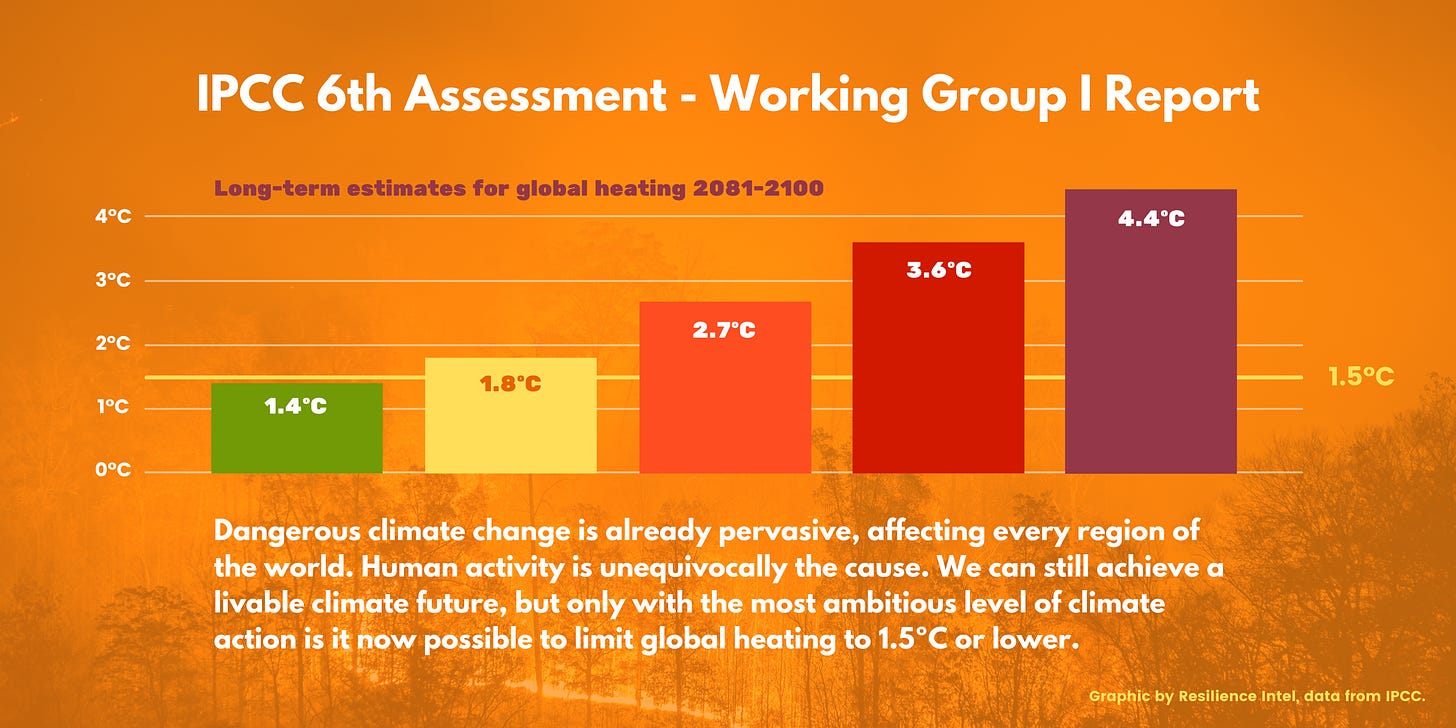

There has been a lot of talk about the 1.5ºC target for maximum global temperature rise no longer being achievable. The global energy crisis, booming fossil fuel profits, and the language suggesting a coming increase in natural gas production, all contribute to these concerns. Emissions are still rising, and the concerns are warranted, but it is wrong to throw our hands up and say “1.5ºC is gone!” It’s not gone; 1.5ºC is still achievable and is still the legally binding science-based goal.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was clear in its 6th Assessment Report that in the best case examined, we can keep warming to 1.5ºC or lower, but only after we see temperatures rise to 1.6ºC. We can still decarbonize fast enough, especially if we do better than 50% emissions reductions below 2005 levels by 2030.

In fact, the current global energy crisis—which has pushed prices up across all sectors—is demonstrating the urgent need for countries to achieve energy sovereignty through clean energy systems that are more adaptive, efficient, cost-effective, and capable of prioritizing decentralized domestic production over imports tied to market fluctuations driven by cartels.

New spaces to drive change

In his remarks to the Closing Plenary, Simon Stiell, the new Executive Secretary of the U.N. Climate Change Secretariat, quoted Maya Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning”:

“The horizon leans forward, Offering you space to place new steps of change.”

The words are more than poetry; they describe the way the COP27 outcome could result in transformational forward progress over the coming years. The COP27 does open important spaces in which to place new steps of change:

Though not detailed enough in reference to food systems transformation, the new four-year work plan for the Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture is a clear space to undertake the “comprehensive and synergetic” innovations and actions called for in the Preamble of the Sharm el-Sheikh text.

The detailed call for transformation of International Financial Institutions will be critical for most efficiently curating capital flows to address countries disparate and overlapping needs relating to mitigation, adaptation, loss and damage, and resilience-building.

The COP27 outcome for the first time recognizes “the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment”; this is an invitation for national and international cooperative action to safeguard and advance that right.

On international cooperative climate action, work has advanced under Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement, with a diversification of the tools and instruments recognized as “non-market approaches”. Such “NMAs” were described by the U.S. as “not quid pro quo emissions trading” but rather cooperative direct interventions that enhance overall capability. NMAs can be suites of policies, incentives, and direct investments that improve conditions for the mainstreaming of climate-smart finance, trade, and practice, across whole economies.

In parallel processes, we also saw important progress.

Though not formally adopted as legal standards, new recommendations from the UN High-Level Expert Group on net zero integrity are rigorous and lucid. They note we will not be able to keep to 1.5°C if accounting manipulations are possible and emphasize real-world physical reductions in emissions, to reduce the geophysical impact of our industries. Offsetting should be used only to facilitate additional emissions reductions beyond those needed to align with 1.5°C and then only in limited verifiable cases.

The Global Center on Adaptation and the African Development Bank announced new funding up to $25 billion to accelerate adaptation action in Africa, and adaptation-related finance and commerce gained unprecedented attention. Such activities can create value that supports economic progress across all of society, and they can be bolstered by financial innovations being sought across the international financial system.

The High-Level Climate Champions have stewarded an impressive list of new climate action initiatives by non-state actors, and point to the emerging “all of society” approach to cooperative climate crisis response.

Also external to the COP process, the Good Food Finance Network activated the work plan for creation of a Co-Investment Platform for Food Systems Transformation, to crowd in funding from public, private, multilateral, and philanthropic sources, to support the mainstreaming of healthy, sustainably produced food.

Our delegation’s work

We will produce a more detailed report on our activities in the coming days, but we need to close our COP27 outcomes brief with a note of gratitude to the diverse and hard-working Citizens’ Climate delegation.

Our team included civil society observer delegates from Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Europe, spanning four generations.

A core team managed The People’s Pavilion—with support from the VoLo Foundation and a coalition of partners—which curated hundreds of events with live-streaming, and gave access to those events to hundreds of registered virtual participants.

Our Pre-COP27 Climate Diplomacy Workshops, co-convened with The Fletcher School at Tufts University, prepared hundreds of participants and remote observers and provided critical emerging insights that later played out in the substance of the negotiations.

On November 10, we published Capital to Communities—The 2022 Reinventing Prosperity Report, building on nearly three years of listening and engagement with our network of stakeholders across 6 continents.

Our team advanced the cause of robust, diverse, and trackable Action for Climate Empowerment work—for better public information, education, and participatory process.

We brought to the sidelines of discussions on the Global Stocktake the need to welcome and leverage integrated and holistic approaches to climate action, at all levels, prioritizing the voices, knowledge, and needs of stakeholders.

And, we consistently brought the word to negotiators and observers that non-market approaches under Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement hold promise to mainstream climate resilient development across regions and between income scales, and so deserve attention as potential drivers of other critical areas of implementation.

In the closing hours of the COP27, our team also focused on the meaning of small changes in language, and how to carry forward the work of high ambition advocacy.

Above all, we can say we achieved our primary organizing goals:

To be coordinated and capable, no matter how unruly the process itself might seem;

To bring diverse voices and perspectives into the rooms we were in, consciously representing our co-constituents back home;

To advance critical areas of inclusion and innovation, to strengthen prospects for future success.

What’s next

In the coming weeks, we will zoom in on specific areas of the COP27 outcomes and the work toward COP28, highlighting catalytic breakthroughs and emerging opportunities for innovation and action. We will continue our work to advance the human right to a livable future, building on the right to a clean and healthy environment and the Loss and Damage breakthrough.

On Monday, November 28, we will launch a year-long Global Consultation on Priorities for a Livable Future. Click here to learn more.

On Monday, December 12, we will hold our next monthly meeting on Non-market approaches under Article 6.8 of the Paris Agreement. Use this form to register your interest to join.

We invite you to send a letter to the G20 Leaders, asking them to Follow the Money and transform finance to fund loss and damage and mainstream climate-smart transformation.

Our daily briefings and other COP27-related materials, including a file of select formal outcome documents, can be found at ctzn.earth/cop27-briefings